A good rule for Uber safety — and life generally — is this: Memes are not facts.

Take a minute to imagine this situation. It’s probably familiar enough, if you hark back to the ‘good old days’ before COVID-19:

Your Uber pulls up. You know it’s the ride you booked, because the number plate and car model match the information provided in your smartphone app. You always check it before approaching the vehicle. Maybe you also snap a photo of it on your phone, hit ‘forward’ and type in your travel destination, then send it off to your nearest and dearest. (Or, you might just use the Uber app’s ‘Share My Ride’ function.)

Either one is easy enough to do as you wander towards the car. Perhaps you even make a point of letting the driver see you do it. After all, prevention is always better than cure. It can’t hurt to make it clear that you’re not an easy target.

Next you open the rear passenger-side door. You choose that seat because if your driver is a predator, they can’t easily reach you. And, the line of sight from there will give you the most direct view of their hands. You’ll be able to read their body language without your own being obvious.

When it comes to safety, you’re all over it. Even if Uber’s 2019 report (done in conjunction with the National Sexual Violence Resource Center) said that only 3,045 of the USA’s 1.3 billion annual Uber trips involved a sexual assault — and half the time the driver was the victim — you don’t want to be among the unfortunate few. Plus, you know that around 60% of sexual assaults still go unreported in the USA, and the same is true Down Under. That may still equate to a very low number where Uber is concerned, but you’re not one to rely on probability.

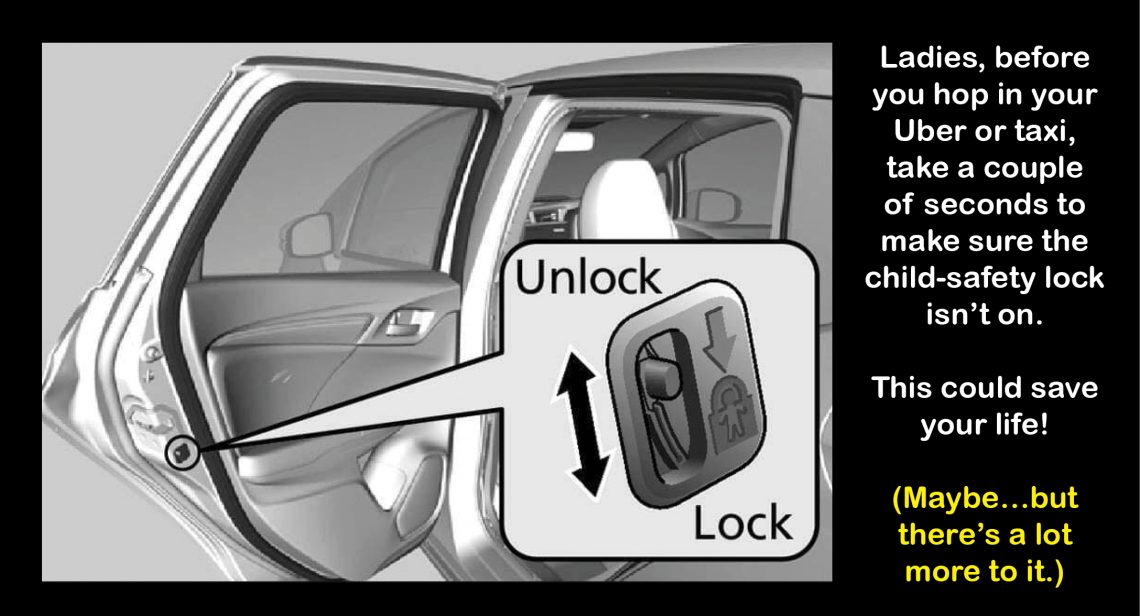

So, now you’re going to do that thing you saw on Facebook. You look down the inside edge of the car door to locate the child-lock. Is that it? It doesn’t look like the one in the picture. That must be it…but is it on or off? Can’t see an arrow — it’s too dirty. You quickly rub off the dirt…but can’t get a clear view looking down from this angle. Is it up for off and down for on, or the other way around?

Planning to Fail

There is an old saying that if you fail to plan, you are planning to fail. And as you stand there holding the door, confused, it might seem to hold true when it comes to Uber safety.

Now your driver starts talking to you: “How are you going? Where are we headed today?” Not wanting to look paranoid or socially awkward, you switch your focus to answering him, and just get in the car. Then you realise that while thinking about the door lock, you forgot to ask the driver his name — and whether he knows yours. That’s something you always do. It’s a basic precaution; another opportunity to reveal any ‘red flags’.

You also realise he’s wearing a P2 mask over the lower half of his face — nothing unusual since the caronavirus hit, but it makes him hard to identify. You can’t ask him to remove it; it’s reasonable protective equipment for the job. Not to mention, ditching it could reduce your Uber safety more than anything else, right?

Now, not only are you unsure whether your driver is the guy in the app profile, but you have no idea whether you’re locked in his car. You’d never thought about it before, but now it’s making you feel uneasy. You touch the tactical pen in your hip pocket for reassurance — at least you’ve got Plan B, your glass-breaker.

Now, rather than think this scenario through to its darkest possible conclusion, step back out of your imaginary Uber for a minute. Let’s look at the missing elements here: training and preparation.

The fact is, any of us could end up in a similar situation to the one described, if we try to execute a new process without first working out the steps involved, let alone practising them. In this scenario, you’re also unaware of likely variations in the mechanism that’s central to your task — the lock itself.

To top it off, you’re trying to do it under pressure.

The Mitsubishi child lock, how you'll really see it

Social Butterflies

Why would pressure be a factor in the failure to execute your door-checking plan? You’re just getting in an Uber, after all. But, the fact is, you’re a social creature in a social situation. This element should never be overlooked in a tactical assessment of any situation because, for most of us with normal levels of social conditioning, this behavioural hardwiring has a huge influence on how we act and react. Whether you defer to your own experience or the many scientific studies of this phenomenon, it’s hard to deny: we rarely do anything in public without considering how it will be viewed by others, or how it might cause them to react.

This is why some of you may not cross the street even when those ‘gut butterflies’ tell you that the person you’re approaching is a potential threat. We humans are odd that way. On some level, we care about the impression we give to people we’ve never met and will likely never see again. Innate behaviours that generally help in our species’ survival — in this case, to reduce chances of social rejection — can also work against us.

Relating this back to the Uber safety scenario, the combination of confusion and the feeling of social pressure (which, in this case, equals time pressure) increases the likelihood of stuffing up at a critical moment. This is why our tactical plans must account for our social realities —and our personalities, too — if they’re going to work.

Know Yourself

Let’s take the scenario back to the first step: getting in the car. Maybe your choice of passenger-side back seat isn’t the best of all options. The driver could possibly still aim a gun at you from there, right? That’s unlikely in Australia, but still… Maybe it’s better to do the typical Aussie thing and jump in the front, where you might be in better position to initiate a quick response if your driver starts acting dodgy.

Perhaps you’re not confident enough for that, though. In that case, why not seize the ultimate positional advantage by scooting over to the seat directly behind the driver? Because that could seem weird. At best you’d come across anti-social; at worst, the driver might think you’re the one planning an assault.

Are you willing to be the weirdo for a slight tactical advantage, ‘just in case’?

Probably not.

So, when you’re working out your Uber safety plan in your head, be real with yourself. Ideally, you’ll be confident enough to set your own rules in these situations, unburdened by others’ opinions. But more likely, you’ll have certain limits when it comes to kicking social norms to the curb.

In Kinetic Fighting, we usually talk about the potential for misalignment of mental and physical capability in regard to combative techniques. For example, everyone has the physical strength in their thumb to gouge an eye, but a lot fewer — if they’re honest — have the mental capacity to do the deed.

It’s important to seek mental–physical alignment for combatives training to be effective, and no less so when it comes to the social conditioning aspect of our mindset. That being said, there will always be times when we have to take action we’d rather not. Being prepared is only partly about acknowledging our limitations; to be effective, we’ll inevitably need to push past some of them. That’s how a ‘combat mindset’ is developed.

Preparation vs Assumption

Rarely does any ‘new’ behaviour happen without training. If you simply noted the meme about child-locks and thought, ‘right, I’ll be safer when I travel from now on’, you’ll most likely be mistaken. And the moment the advice is needed is exactly when you’ll come to this realisation — at the wrong time, in the wrong place.

Remember, every such situation has a social element. So, have you rehearsed or visualised how to make your pre-journey checks in a subtle way? Or, if you’ve decided to make them overt, are you prepared to deal with any awkwardness or questions that follow? You might be the type to not care — but if you do, how will you handle it?

And what if the driver tries to tell you where to sit (regardless of the reason given)? Are you prepared to stand firm, and send him on his way if he insists on compromising your safety protocols?

Every car model is a bit different, too. So, have you familiarised yourself with common car-locking mechanisms on a number of different vehicles? And on sliding doors too? If you look at the photos above, from just two different vehicles, you’ll see how placement, angle, lock direction and visibility can vary — a lot.

Uber Safety, sans Paranoia

Having an Uber safety plan — with a few contingencies for potential failures — will certainly increase your ‘survivability’. Awareness and avoidance are the cornerstones of any decent self-protection system. But of course you can’t think of every possible scenario, nor prepare for them all. And if you try, you’re likely to become paranoid and ever more fearful of what you don’t know, rather than reassured by what you do.

That’s why self-protection also requires a mental readiness to take necessary action, no matter where it sits within the ‘force continuum’ of legally justifiable self-defence. Our primary means of protection will always be maintaining a state of educated awareness. A close second is using planned and practised behaviours to avoid and escape situations that compromise our safety. But beyond that, we must also be mentally prepared to break out the glass-breaker — or whatever else we need — if and when the S hits the F.

This state of mind is quite different to paranoia. The latter, over time, will not only reduce our ability to enjoy social situations but to read them accurately, and to separate real threats from the benign. In the end, our awareness of our environment and, especially, the behavioural cues of the people in it (those ‘red flags’ mentioned earlier) is more important than any knowledge of specific threats, such as hidden car locks.

So, be prepared to act but also keep in mind that violence against ride-share users is rare. That way, you’ll be able to enjoy your ride, not just ‘survive’ it.

About the author: A journalist and editor by trade, Ben Stone has been studying and writing about martial arts and self-defence systems for more than 15 years. He was the Managing Editor at Blitz Publications & Multi-Media Group for over a decade before taking on the role of Chief Information Officer for Kinetic Fighting. At BPMG, he produced some of Australia’s leading sports and health magazines, including Blitz Martial Arts, Women’s Health & Fitness and FIGHT! Australia.